Thicc Margins

One of the many reasons we climbed so fast to 7,300+ breweries is because “the big guys” took too long to respond to IPA. By leaving the door wide open from 2011-2015, new breweries saw instant success on the back of that particular style and were afforded the cash flow to expand into some of the strong local/regional players we have today. While AB-Inbev bought Goose in 2011, IPA wasn’t made the priority until 2015, the same year that Lagunitas and Ballast Point were acquired by Heineken and Constellation. Once those and other transactions closed and updated strategies were put in motion, the industry would never quite be the same.

Scale can be a beautiful thing. The term often accompanies terminology that makes number crunchers like me happy such as efficiency, optimization, cost-effectiveness, and great margins. In the first half of the decade, scale wasn’t a threat to small and independent breweries. Sure, regional players like Bell’s could make beer for less than a small operation like Toppling Goliath, but the large formats (22oz bottles) helped even the playing field and allowed plenty of margin for everyone to be wildly successful. Simpler times.

Look at the hottest IPA in the country as an example, Founders’ All Day IPA, who has held that title for an impressive run. Put aside your opinion of the beer itself or whether it fits IPA style guidelines. The beer flies off the shelf, especially as the price pulses down on sale to $13.99 for a 15-pack. Founders can afford to sell at this price because of the capital investments made in their size, scale and process, each of which contribute to amazing yields.

Yield

Yield is a concept that I never thought about once prior to working on the supplier side, but have learned that it's a fascinating topic that technical brewers obsess over. A batch's yield calculates the amount of ingredients that survive the various stages of brewing, often measured as a % of the inputs used. Yield is determined not only by the amount of usable extract that finds its way to the fermenter, post brew, but it accounts for the losses that occur at each stage during fermentation and packaging as well. The larger and more sophisticated the operation, alongside investments in process, the less loss incurred. A high yield means that a lot less beer is going down the drain, instead of the package. Overall cost per barrel goes down and margins go up. Free beer, sort of.

Margin - 3 Tier

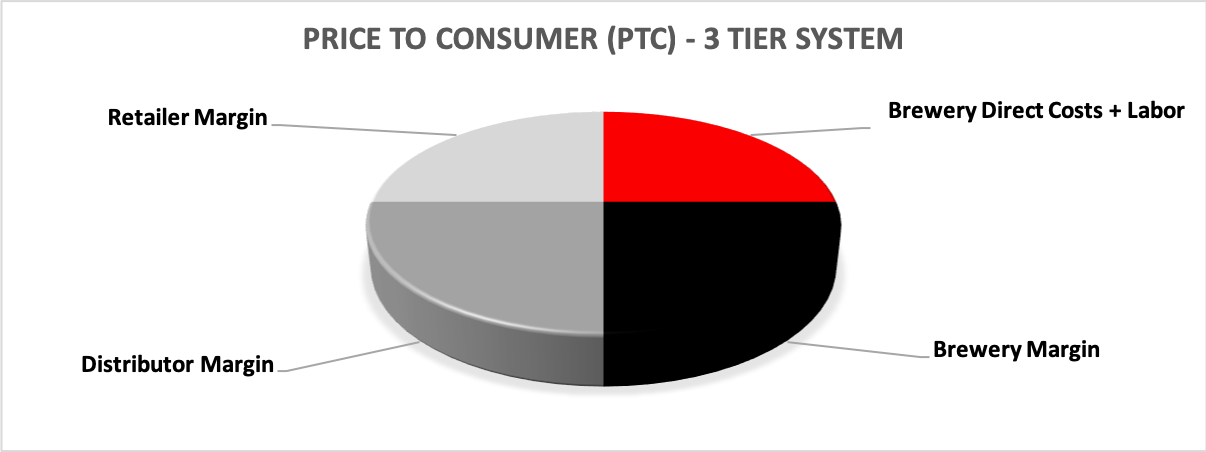

Breweries achieving scale require a lot of help to move all that liquid. If you see tanks that are taller than the brewery itself, it’s a safe assumption that significant portions of that beer is being sold in chain stores. Long-term success in that channel will usually require a strong distributor, thus sharing the margin with two other tiers. Exceptions tend to only occur in local markets, like Stone in Southern California and Rhinegeist in Cincinnati. By following this model of scale and efficiency, you have to learn how to make your business work under the following parameters:

Don’t get too hung up on the above graphic as margins vary wildly by brewery/distributor/retailer and each specific beer/style/format, but I believe this is a fair, yet over simplified, way to break down the price paid by the consumer for craft beer passing through the 3 Tier System.

The majority of the price-to-consumer (PTC) is taken up by the input costs, distributor margin, and retailer margin. The brewery relies on volume (and efficiency) to earn the margins required to build and maintain that size of an operation, support it with sales & marketing, run the backend, and service the debt/investors that can come along with running a brewery. None of those are included in the red slice and instead come out of the black.

Margins - Self Distro

The self distribution model provides smaller breweries with the ability to hang onto an additional slice of that pie. By cutting out the distributor, they’re able to compensate for discrepancies in beer costs between them and larger peers, while still running a solid, albeit smaller business. Self-distribution also provides significantly more control to the brewery as to what they brew, package, and sell to retailers. They control the conversation, can move at lightning speed, make beers on somewhat of a whim, and react fast without having to get their distributor on board with the prospect.

It’s not all gravy, as the more beer you’re selling, the farther you are probably reaching and sending vans or trucks. Deliveries can be efficient in a densely populated area, especially if that’s where your brewery is located as well, but as you extend farther out, you give up your route profitability and spend more to make less. Depending on the leadership and expertise at the brewery, adding a logistics arm to the business may eat up too much focus and cause unnecessary headaches, but a growing number of breweries have taken on the challenge and successfully used it to their advantage.

Margins - Direct to Consumer

Now it’s time for dessert. Those sweet “own premise” margins that leave you with a pacman-looking portion of the pie, all to yourself. The cheapest and most flexible form of packaging, a stickered can, happens to be the most desired right now. Consumers come directly to you, you maintain complete control of the pipeline, and you keep all the gravy. Sounds amazing, as long as they show up...and continue showing up...

There were days when beer enthusiasts would enter raffles or wait in long lines just for an opportunity to buy a clear, citra-hopped Double IPA. Then the farms grew more citra, everyone got ahold of it, and you could find grocery stores lined with citra IPAs. Though still well-liked, citra is everywhere, and doesn’t necessitate a trip to the brewery to get your hands on it. Citra went mainstream.

Staying more consistent over the years, in terms of consumer interest, is barrel-aged beer. Build a reputation for quality, innovation, and customer experience, and I can tell you first hand that they will come in droves. But the significantly delayed cash flows and other constraints of barrel-aging is going keep it more seasonal or sporadic for small breweries and isn’t something that can keep the lights on and drive the business. Small operations need beers that can be produced and turned quickly until they can afford to be that patient. Finding styles that will keep enthusiasts showing up is the moving target that thousands are trying to keep up with now.

Similar to how macro breweries ignored IPA until 2015, the Top-50 craft breweries mostly ignored New England IPAs from 2015-2017, leaving those big margins to “the little guys” while expecting the buzz to die down. The style represented a threat to their competitive advantages, including scale and process. It threatened traditional techniques, shelf stability, and margin through the 3-Tier system. Heavy losses incurred by multiple aggressive dry hop additions make the costs of New England IPAs very high, given the terrible yields that result from a lot of expensive ingredients going down the drain. When a brewery’s size yields batches too big to sell out of your own building, it’s hard to make inefficient, poorly yielding beers work at the 3-tier margin. For small neighborhood breweries whose consumers flock directly to them, it was the perfect recipe.

But when there’s sharks in the water and they smell blood, they find a way to make it work and they have. Hazy Little Thing kicked the door down and proved that the market for haze stretched well beyond beer enthusiasts. Once enough IRI data came out showing the continued torrid pace of that brand, through expanded distribution and impressive velocity, it wasn’t long until the others took a big bite themselves beginning toward the end of 2018.

Hazy interest remains sky-high, but saturation is already peaking its ugly head and the sell-through isn’t quite as automatic as it once felt. Now that you can buy Hazy IPAs at the grocery store, the style will begin to feel more like IPA in general, competitive as hell. Sure there will always be high-end versions, but with delicious hazy beers widely available from national(ish) breweries like Firestone Walker, Bell’s, New Belgium, Oskar Blues and Sierra Nevada for the likes of $9.99, how do the small guys and gals compete with that? They don’t. They swim away from the sharks into shallow waters. A significant subsection have wisely been going after for the younger demographic, heavy on rotation, with eye-catching artwork, visual cues, themes, and a sweet flavor profile.

Enter Milkshake IPA

The latest “spin” on the extended IPA family is typically brewed with lactose, pectin, or oats for a full-bodied, almost chewy drinking experience. Vanilla is commonly added, in addition to fruit and other non-fermentable sugars to build that sweet flavor profile. Like’em? Hate’em? You won’t hurt my feelings either way, but this is how you drive the 20-something, new-school beer enthusiasts to your brewery today. Throw in the heavily fruited, Jamba Juice-like kettle sours, along with pastry stouts, and you’ve got a trio of very different beer styles that have a lot in common. Not only do they all lean sweet, but they’re each a challenge for larger breweries to bring to market.

Those currently making Milkshake IPAs can’t compete with regional or national breweries on price, nor do they want to. By offering these unorthodox styles at a pace that large breweries can’t keep up with, they find a different audience who is in search of that eccentricity. Milkshake IPAs are not some advanced level in the evolution of beer enthusiasts. They’re a new entry point into the hobby for the youngest generation and a new option for breweries to capture the thickest, err...thiccest part of the pie. Brewery openings are starting to slowdown and taprooms will lose that new car smell, meaning small breweries will need to keep innovating, stay nimble, and use freshness to their ultimate advantage.

I’m not in love with Milkshake IPAs myself, but I have had a few recently that I found fun and interesting. I understand why there’s a market for them and think they’re a creative means to build a younger fanbase. They’re keeping a sector of small breweries competitive in a time when large breweries are reacting quicker to trends and acting smaller than they ever have. Unlike a double or triple dry hopped Double IPA, Milkshake IPAs don't require as many hops and yield significantly better. As we saw with Brut IPAs, the largest craft breweries in the country are prepared to pounce quicker than ever to remain in the conversation. Thanks to even better margins and the need to stay on the cutting edge, the same thing will happen with Milkshake IPAs, once we’re past this current stage of denial.